I’m embarking on the highest altitude trek that I have done so far, in Bhutan. I will be hiking along with a Bhutanese guide (required), and a mountain pony to carry the tent and food. I will carry my own gear in a backpack. As you can see, we’ll be camping many nights at 13,000 feet or higher, and hiking up over some very high passes, including one 16,420 feet high. I am going to place a Buddhist prayer flag for Judy per tradition on the highest pass, and scatter some of her ashes there.

I hope that I will be able to avoid altitude sickness by hiking up gradually. The second day, with a 3,000 foot altitude climb, is my main concern. I have medication along with me that can help. For those who don’t know: altitude sickness occurs at altitudes above 10,000 feet, and is due to the reduced amount of oxygen available up there, only 50-60% of that at sea level. The symptoms are headaches and nausea/vomiting. It is a potentially fatal malady that you do not want to endure. If you climb gradually, no more than 1,000 feet a day, it is possible to acclimatize and avoid it.

So why go to all this effort? Well, Bhutan is more than half untouched by roads, some of the most pristine mountain area in the world. I must warn my readers: don’t attempt this unless you are very fit, as it is quite strenuous.

(Note: I have come out of the high country now, and will begin posting pictures. Check periodically for more. This will be a long, detailed post, as I realize most of my friends will not make it up into this high mountain area, and will be interested in many pictures and details.)

Before heading up to the trailhead for the trek, we overnighted in Paro. This is the Paro Valley. I was surprised to see many rice paddies at this altitude.

A painting on the wall of the hotel dining room in Paro. A nice overview of Bhutan.

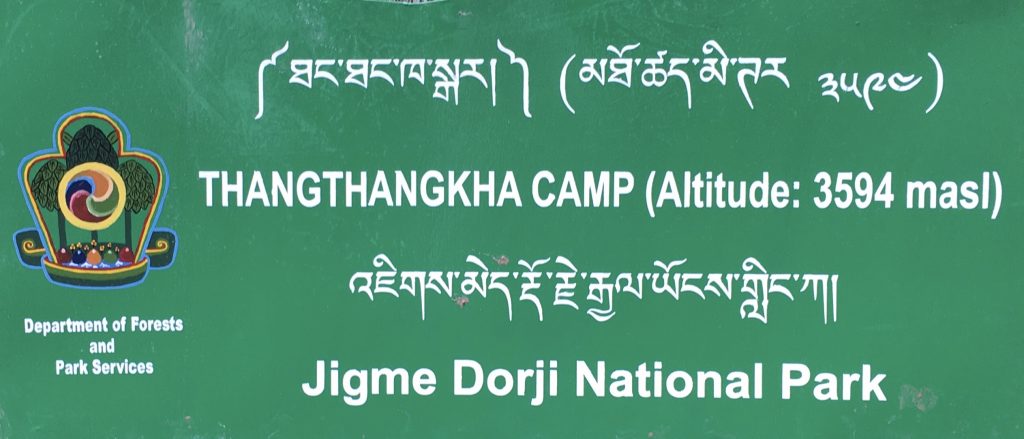

Jigme Dorji National Park is about the size of Glacier National Park in Montana. It covers 11% of the area of Bhutan, and is unusual in the sense that 6500 people live within its boundaries. These are mostly nomadic Yak herders. It is roughly 40 miles square. Due to the fact that there are no roads, and the terrain is extremely rugged, it seems much larger. Supplies are brought in on pony/mule/yak back.

Here are a string of pack mules & ponies on the trail, led by this lead mule. The trails are very rough, and the ponies do amazingly well to negotiate the steep, rocky terrain without injuring themselves. In one case, we saw a pony tumble down a slope when the edge of the trail slid off. Fortunately, it was not injured, and was able to walk back up and rejoin the string after being repacked.

This is the standard pack saddle, made of a tough wood. The straps under the tail and behind the rear legs keep the load from sliding forward on the steep trails.

Each pony carries about 110 pounds cargo, which is, of course, a bit less than one average rider. The pony handlers almost always walk the trails behind the string, rather than riding.

At the higher altitudes, we began seeing yak pack animals. The yaks are bigger than the ponies, and do very well even on steep slopes and in snow. It was funny to watch them, as they didn’t really care that much about following the trail—they’d just as soon traverse along the steep hillsides off trail!

Yak grunts, with a loud river in the background. Imagine hearing these around your tent at night, mingled with pony bells.

Yaks come in many colors and sizes. They are superbly suited to this high, rugged terrain. The nomadic yak herders move them up to the high slopes in summer, then down lower in winter. They are milked, and the yak butter is sold at a higher price than cow butter.

A couple of kids on their way to school, from a home in the lower Paro river valley.

Immediately, my naive ideas that my trek would be me, a pony and a guide hiking were set straight. It was more like an expedition: me, a (required) guide, an assistant who helped around camp and carried a hot lunch and tea on the trail, a trail cook (who was quite good), a horse handler, 3 tents, and 6 ponies to carry all this! This is the standard trekking setup in Bhutan. Kind of like a cross between backpacking carrying all your gear and food, and car camping, as you have all this heavy gear available. Hikers carry their own water for the day, as well as several layers of clothing for the changing conditions. Sleeping bags and such are on the ponies. When you are breathing hard at 14 or 15,000 feet, you appreciate that!

My trekking team: Kinzang, our cook, Tenzin, our assistant, Rigzin, my guide, and Kaka, our horseman.

The blue tent is for cooking, and later sleeping. The orange tent is for eating, and later sleeping. The green tent is mine. There was also a very small toilet tent that was set up over a shallow hole dug in the ground. Each morning, we broke camp, loaded the ponies, and set off to hike 10 to 14 miles plus often climb over passes with climbs of 3,000 feet and more. At these high altitudes, you must hike slowly and breathe faster to get enough oxygen, so we typically hiked 5-7 hours a day, with a break for tea and later lunch along the trail.

I had not realized how spicy the food in Bhutan would be. Here is one typical trail meal. Take a skillet full of hot red and green peppers, sauté them in a white cheese sauce, and eat this delicious Thai-hot ‘chili cheese’ dish. Yummy, very spicy.

This is the result (in a cafe). The white part is made of eggs, and there are also mixed vegetables. All in all, I found plenty of tasty food in Bhutan. I never got around to drinking Yak butter tea, which is more of a Tibetan thing.

We crossed many glacial streams, sometimes hopping on rocks, sometimes on bridges across the bigger ones.

There were a number of ‘cantilever’ bridges, quite interesting. They look road-size, but there are no roads in miles. They are wide for the benefit of the pack animals.

They have severe winters here. Flooding destroyed this bridge last winter.

Campsite day 2. 3594 meters high is 11,791 feet in altitude. Getting up there! That is higher than Mount St. Helens ever was. I met a man here who had descended from Jomolhari Base Camp due to altitude sickness: nausea, headache, and blurred vision. His wife was OK, and was continuing, but he had to stop. There were also two helicopter evacuations of people who were suffering from severe altitude sickness while we were on our way up. You must take it seriously, as you can die from it overnight.

It had rained for two weeks just before I arrived. I caught the last two days of that, and then no rain for the rest of the trek. But it left the riverside trails very muddy, a big bother! A nice mix of mud and pony manure, kind of like a Washington barnyard in the winter. You hopped from big rock to rock to avoid sinking in. No point in cleaning your boots off at day’s end. My least favorite part of the trek. As we got higher, we climbed above the mud.

Last year, a power transmission line was installed along the Paro river valley. I think they could have done a better job of keeping it off to the side, out of view, and I’m going to try to do something about that for future lines. There is no need to spoil the beauty of these beautiful valleys.

The Paro Chhuu (river) valley is steep, rocky and dramatically beautiful.

Day 3 campsite was Jomolhari Base Camp. Altitude: 13,451 feet. The air is getting thin! Only 6/10ths as much oxygen up here as at sea level. This was the test as to whether I would get altitude sickness (due to going up too fast). That evening, I began ‘urping’, which I’ve seen as a precursor to nausea/throwing up. Not wanting to risk that, I decided to use Diamox. Within an hour, the urping went away. Diamox works for me, no ill side effects I could notice.

In the morning, we caught a glimpse of Jhomolhari, 24,000 feet high, just up the valley. A big part of the fun of this trek was seeing this wall of spectacular peaks that form the border between Bhutan and Tibet.

Jichu Drakye, 22,930 feet high looked particularly hard to climb.

Some fresh snow up high last night dusted the plants with a corn snow about the size of sesame seeds.

And into the snow on some passes. In winter, this is impassible except for yaks.

This is Sinche-la Pass, 16,420′, the high point of my trek, with Tiger Mountain, 22,440′ in the background. A Buddhist note: multicolor prayer flags like this are praying for good luck. Large clusters of white prayer flags are for people who have died, to calm their suffering and help them be reborn sooner. Single pole flags of any color are prayers for longevity. On this pass, you see mostly good luck flags, with some white ones, as the ones I put up for Judy.

Judy’s prayer flag.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_video link=”https://vimeo.com/189352035″][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Archery is the national sport of Bhutan. Archers stand 165 feet (more than half a football field) away from a 1′ x 2.5′ target and shoot. It looks impossible! The bows are American compound bows these days. The first shot is slow-mo. Then, if someone hits the target, their team members do a song and dance to celebrate.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_video link=”https://vimeo.com/189417648″][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

These local girls are headed over to watch the archery contest. Maybe a good chance to meet cute boys? You can see a mix of traditional dress and modern down jackets. How they keep the hems of the dresses free of mud mystifies me. It must be grace.

One of the vast high hills areas swept by wind and winter snow. The north facing slopes you see here have big areas of rhododendron that flower red in April. In October, they are the dark green patches in this picture.

Glacial streams have a milky grey-green color due to the glacial till (ground up rock) carried in them. This one is from glaciers on Tiger Mountain.

If you’re lucky, you can see herds of ‘blue sheep’, actually a kind of antelope where the males have long horns and a slightly bluish tinge to their winter coat.

A trail obstacle. The yaks are actually quite docile and easy to boss around.

One of the settlements of yak herders.

We stopped for morning tea here. I joked that this was where I wanted to build my cabin.

Nice view.

One of the rare local pony riders. As he is not in traditional dress, I’m unsure what he is doing, as he has no baggage.

Some young children got to ride, but a lot of them walked the trails along with their parents.

Laya is the highest village in Bhutan at 3800 meters, at 12,500 foot altitude. It is the home of the Layap ethnic group of yak herders. They wear distinctive clothing colors, and women wear a special hat:

I presume that is not a lightning rod on top.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_masonry_media_grid grid_id=”vc_gid:1477901221170-dcab7539421f6cd45c29504f8a8ff094-0″ include=”3469,3471,3467,3466,3468,3465,3464,3458,3459,3460,3461,3462,3463,3457″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

In Laya, I stayed two nights in this home that rents out a room upstairs. It was an opportunity to see how the local people live, and was also warmer than my tent!

The living area is upstairs, up this way.

My room upstairs.

The kitchen. We gathered around the wood stove in the cold evenings. I gather this woman cooks for feast days, explaining the very large collection of pots.

My hosts. He owns 19 ponies, and we rented 6 of them for the trip from Laya via Koena to Gasa.

The King came to visit, so a special house was made to accommodate him and the Queen.

A vegetable patch. This village now has electricity, but no road access.

Kids doing their clothes washing chores.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_masonry_media_grid grid_id=”vc_gid:1477901221273-d18779ca6ea197886d0ccb54d601aa90-5″ include=”3381,3385,3386,3388,3379,3370,3368,3369,3367,3365,3346″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Yes, if you can do this 33 mile uphill rough terrain run from 8,850 foot elevation to 12,500 feet, you are certainly a marathoner! Walking it downhill was enough for me.

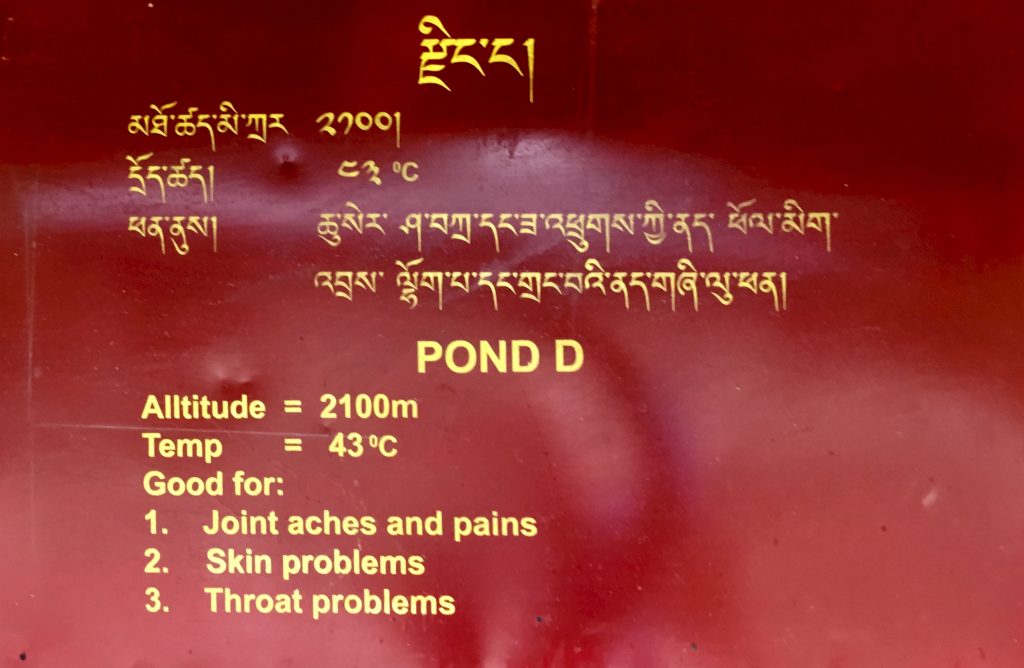

Our last night was in Gasa, near the hot springs. The whole gang was looking forward to a nice long soak in the natural hot water.

Only the King gets to use this entrance.

I have become a big fan of Japanese-style very hot water, as in their natural ‘onsen’ or hot springs baths. So I went for the hottest pond, which is about 109°F. Ah…If it doesn’t cure all the above in one visit, well, I guess you’ll just have to keep coming back till it does!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.