My nephew Reuben and family now live in Rising Sun, Maryland, about 60 miles north of Baltimore. I journeyed down by train and car a few hours south of New York for my first visit to Delaware and Maryland. It’s just 1 ½ hours by train from NYC Pennsylvania Station to Wilmington, Delaware. The first part of the journey takes you through industrial New Jersey, past oil refineries and manufacturing plants.

Rural Maryland near Chesapeake Bay used to be mostly big 300 acre farms. While it has begun to be subdivided, many big farms remain. Just two miles south of the Pennsylvania state line, it is not far from the Amish and Mennonite farm areas. While driving there, I passed an Amish horse and buggy.

A Mennonite family at the Wilmington, Delaware train station

Maryland lies just north of the Mason-Dixon Line, but though they were part of the northern Union States, they were allowed by law to hold slaves prior to the Civil War. This old fieldstone house in Rising Sun, Maryland build in the 1700s had slave quarters in the third floor attic.

This big field adjacent to Reuben and Sheila’s home is fallow, awaiting a crop of field corn or soybeans. In season, the crop tops are alight with fireflies at night.

Big open farmland spaces

[vc_video link=”https://vimeo.com/173401035″]

A snippet of “Coat of Many Colors” song, sung by Abby and mom Sheila.

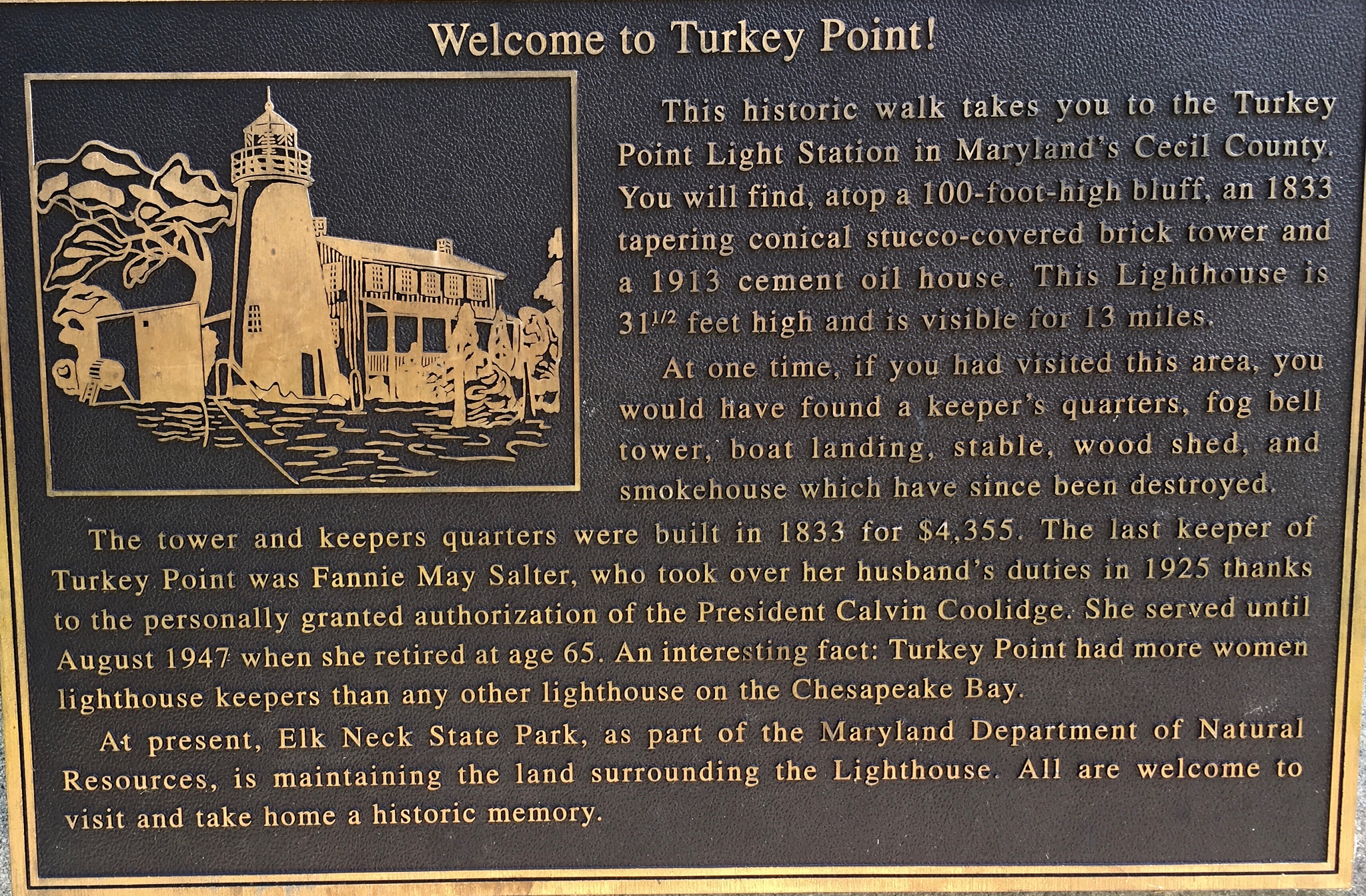

On a sunny, chilly May day, we drove out to Elk Neck State Park and walked about a mile out to the Turkey Point lighthouse. It can get very windy out here!

Lots of history here on Chesapeake Bay

Spring has sprung, and flowers are forming on the trees.

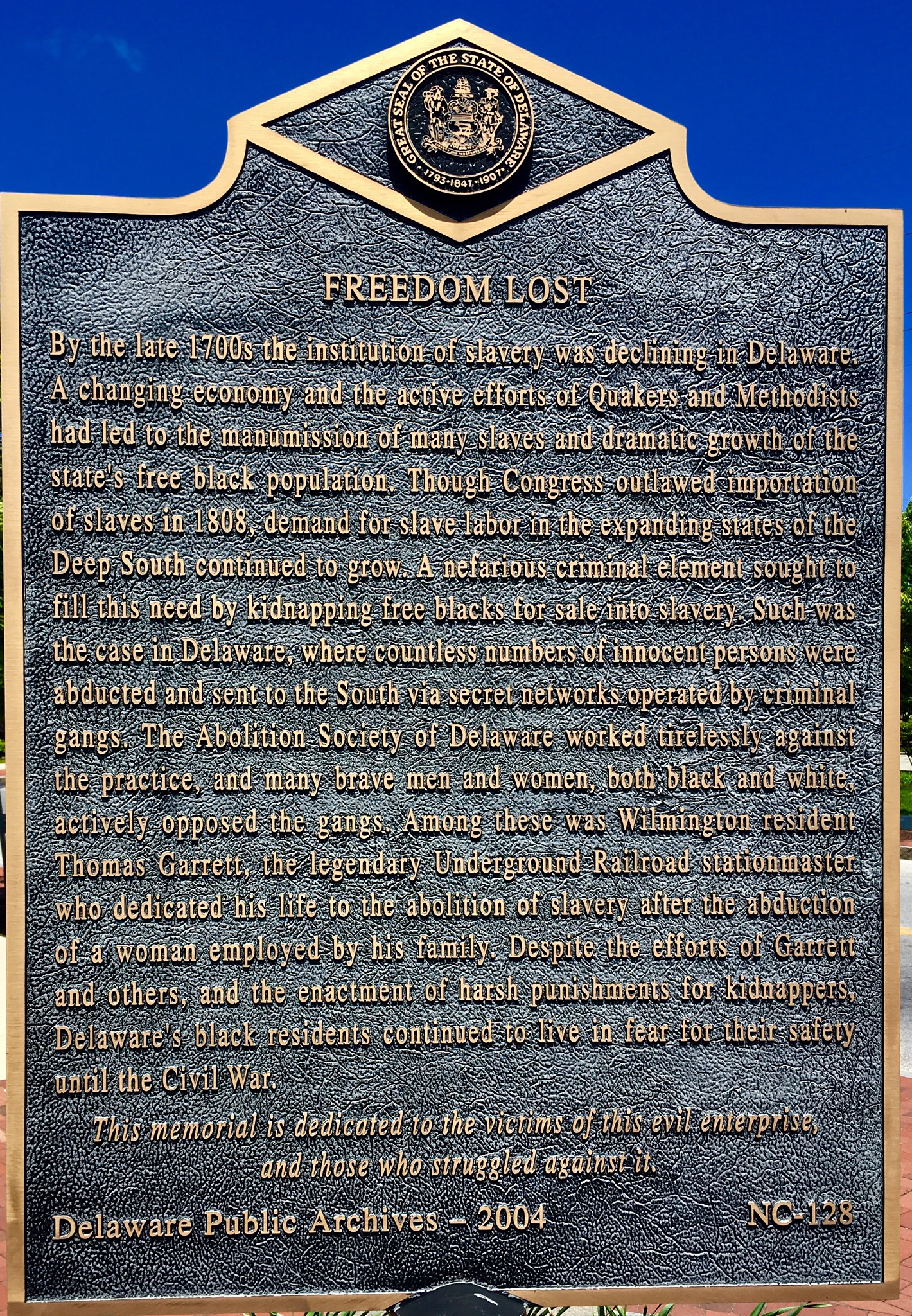

Now, the time has come to head back north via Wilmington, Delaware. While waiting for the train, I took a walk down by the riverfront and learned some history

I had not known that the importation of slaves had been banned in 1808, or that trade in slaves had continued for the next 50 years despite that. It is hard to imagine what it must have been like to live in constant fear of being kidnapped and separated from your family and children, and forced to work as a slave in the areas where blacks were treated as property with no rights.

Thomas Garrett, a Wilmington, Maryland Quaker and iron merchant, decided in the year 1820 to devote his life to the abolition of slavery. Over the next forty years, though often threatened with physical violence, he helped more than 2,000 blacks reach freedom in his capacity as ‘Stationmaster’ in the Underground Railroad.

Even when in 1848 he was fined so heavily that he lost all his property, Garrett declared to presiding judge (the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court) that “…thou has left me without a dollar…I say to thee and to all in this courtroom, that if anyone knows a fugitive who wants shelter…send him to Thomas Garrett and he will befriend him.”

(The courage of this man, and the enormity of his sacrifice, touched me deeply)

The Underground Railroad was a network of people–whites, free blacks, fugitive slaves, Native Americans and religious groups such as Quakers, Methodists and Baptists, organized to provide safety and comfort to slaves escaping to freedom.

It was dangerous work and over the years dozens of ‘agents’ were jailed for aiding escaping slaves. Though Delaware was by law a slave state, more than fifteen Underground Railroad ‘stations’ have been identified in the state, testimony to the extraordinary moral courage of many of its citizens.

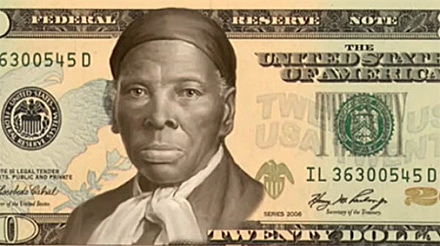

Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman and Thomas Garrett–one, a black fugitive slave ‘conductor’ and the other a white Quaker ‘Stationmaster’–were critical links in the Wilmington area. As a key transportation hub to points north, Wilmington was one of the most dangerous passages for fugitive slaves.

Crossing the Market Street bridge was especially dangerous. As the only public roadway across the Christina River into Wilmington, it was an ideal check point to look for runaway slaves.

After escaping from slavery in Maryland in 1848, Tubman made 19 trips into the South over the next decade to lead nearly 300 slaves to freedom. She was one of several Southern agents who became spies for the Union Army during the Civil War while continuing to aid the growing number of runaway slaves. She eluded capture despite the large bounty on her head.

In 2016, it was announced that Harriet Tubman will become the first woman to appear on US currency, on a new version of the $20 bill. The final design will not be released until 2020. Here is one proposal:

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.